lololol interviews #1: Dino

Gentle Sweeps in a Deep Abyss: Interview with Dino

Taipei-based Dino, otherwise known as Liao Ming-he, is a prolific noise performer who has been active since the 1990s, and is a significant figure of the Taiwanese noise scene. With a distinct sound palette and innovative approaches to manipulating sonic space, his instrument of choice is a mixer board that has no input and is instead hooked up to a series of effect processors that create evocative articulations of internal feedback. Dino’s latest album Senko Issha Live / Dino (2018), produced by the independent Senko Issha, is his first label-backed record. Released in the last quarter of 2018, the album features two exceptional solo performances that capture his persistent search for new sound.

AAP sat down with Dino to discuss his boundary-pushing process, and his thoughts on noise, improvisation and the art of listening.

Looking back, what was the Taiwanese noise movement like in the 1990s?

The first, second, and third wave of Taiwanese noise—these are terms and academic arguments that have appeared in recent years. Back in the day, there were very few people involved. The scene only grew larger when we started performing at ET@T [an artist-run space established in 1995 in Taipei City with the mission to support digital art]. Oftentimes the audience consisted of people who made music themselves. The end of the first wave of Taiwanese noise and the beginning of the second are marked by the Post-Industrial Art Festival organized by Lin Chi-wei and Wu Chung-wei in 1995. It was around that time that Lin and others started making electronic music and experimented with many things, like quadraphonic performances and multi-directional setups. Lin and I both agree that we have done too many bad things in the past. There was always a feeling that we were going to hell after every performance. Now we would like to clean up our acts.

You once described performing as a kind of xiu xing (修行), a Chinese term that roughly translates to self-cultivation. What does this term mean to you?

When the same motion is repeated over a period of time, it generates a certain amount of feedback. The action, done over and over again, will also eventually harden. Some people call this kind of repetitive practice xiu xing. With or without performances ahead, I go through the same motions at home and play with my equipment everyday. They are laid out on my desk and never stored away. Over time, my daily practice generates feedback—some element will return in the process, or maybe it won’t. In any case, what I do disrupts my rhythm of life—I would like to set a start and finish time every day, but more often, I play without end and miss dinner. One can sustain this level of passion for one, three, five years; if you can continue into the sixth year, I have deep respect for your radical fanaticism.

For several years, I played around with other things, including calligraphy; seal carving; and the craft of guqin, a string instrument that is attributed to China. Seal carving is very interesting—to me the experience is similar to noise. In the process of slowly chipping away at stone, you create a sound that you can hear not only through your ears but also through your hands. That subtle, tingly feeling is addictive. After a while, I had to stop carving seals, because it was changing my personality and that was quite terrifying. It made me very anal and picky, which made life too tiring.

What are your thoughts on your recent album Senko Issha Live / Dino?

This is my first album released by a record label. In the 1990s, I made a few albums myself. They were limited edition tapes recorded in my studio, and most of it was ambient noise. On one occasion I made a dozen unique tapes while listening to the sound of rain falling on my roof. I repeated this process in another project, creating a series of tapes in relation to one observational point.

My new album includes two recent performances organized by Senko Issha. They happened within one week of one another, and on both nights, I was in a similar set of mind. Side B happened in Senko Issha while Side A was recorded at Revolver, a Taipei music venue. Prior to the Revolver performance, Wang Chikuang, the owner of Senko Issha, told me the lineup was made up of noise musicians. So, in order to complement the situation, I decided to add a fuzz processor to my set. I would say what I do is noise, and that I am punk, but I do not have enough anger to be truly noise or punk. I never had enough anger, at least not enough to form a punk band or make real noise. What I do cannot be sustained by anger, it is not who I am. But I would still say that I make noise and I am punk, because these imaginations cannot disappear, they are what I reach for—if they are thrown away, there would be too much room for change.

Can you speak about your process with no inputs?

The kind of thing I have been doing is quite simple. Using a stereo system, I pan all my sound to one speaker and then use delay to spread it across space and time. Only the first beat of sound you hear is real and the rest is fake, created by effects. Eventually the time difference between right and left speaker evens out and what you end up hearing is something like a wall of sound. Your ears might trick you to think there is still a delay between the two speakers but that is just an illusion. In order to achieve this, the frequency of sound must make the room vibrate. For some time, I would take off my shoes to find the right sound, then begin my performance. What I do depends on the conditions of the space.

Even though I improvise, I do not like the term—in fact, I detest it. In my listening experience, what is described as improvisation often turns out to be more like new-age music. For example, a chord is introduced and maintained until the end. Sometimes this may last up to one hour, and in this timeframe, there are changes in the tonality but not a lot of musicality or interesting sounds. I’d rather go to Taichung and partake in the Indigenous gatherings that involve collective singing. There is much more improvisational merit to their kind of music. There is always someone singing off tune while striving for unison, creating many interesting changes.

What goes through your mind during a performance?

Many rock musicians come to my house to drink with me and complain about things. These are friends I’ve known for some time. They drink on a daily basis, and yet, before going on stage, they insist on a mental state of clarity. Their thinking goes against my understanding of performance. I drink before a show to dull my reflexes, otherwise it would feel like attending a school examination. Presets of perfection do not exist in rock music, or classical music, or any kind of other music performance, unless you have a strong motive, such as if your performance is a stepping stone to meet someone’s expectations. In that case, you must act precisely, but that would be an examination, not a performance. In actuality, I cannot let go of many habits when I perform. These are not habits of listening but habits of my hands. Sometimes when I drink to a certain state of mind, I am unable to suppress my hands from certain motions, and I allow more waiting time in between gestures, which makes for a quieter performance.

What are you working on now?

I am picking up on projects I started long ago, things I’ve always wanted to do. I am looking for new sounds and trying to lock them down. The setup I am using now is inspired by a sense of emptiness I felt after I performed at Asian Meeting Festival in Taipei last August. The emptiness was so strong and relentless, it was as if something that I had insisted on for a while had suddenly been struck down for no reason. So I spent the next few weeks working and invited a few friends over to test a new setup, which I am using now. This was of course not an act of resistance, because I am a man of self-abandonment. However, an abandoned person in a deep abyss will still quietly make gentle sweeps in the waters, creating ripples of dark sensibility. People on the shore may not be able to see these movements, but with close attention they can notice someone swimming beneath, and perhaps there is also someone swimming right above me, and someone swimming right below me, forming a vertical chain. As musicians, we always want someone to give us a hand. It is impossible for anyone to generate things by themselves; at least, it has not happened before, in my understanding. It would be terrible if there were only one chain of swimmers—the future would not look hopeful.

There are many artists today who say they work with sound, and so the question is, what is it that they want to control? Sound can be used to control people, but do you want to control people? For musicians, this question is not so urgent because they have music as their medium. But sound is something very immediate; when you are on a battle field, when you are facing death, it is not a matter of visual signals—you hear sound first. And perhaps, when in doubt, you will look for the source of the sound and stare at it, deciphering whether what you heard was real or not. Of course, there are those who are more visually-oriented, but the majority of ordinary people listen first, and use their eyes to seek validation. And that is something very unromantic.

(update / 2019.03.26)

☯ Dino

Taipei-based Dino, otherwise known as Liao Ming-he, is a prolific noise performer who has been active since the 1990s, and is a significant figure of the Taiwanese noise scene.

☯ 廖銘和

噪音表演者,現居臺北。

噪音表演者,現居臺北。

lololol interviews #2: Alice Hui-sheng Chang

Alice Hui-sheng Chang: Two step forward and one step back

中文訪談請按此

Tainan-based Alice Hui-sheng Chang is a sound improviser, art therapist and co-founder of sound organization Ting Shuo Hear Say. Alice weaves between the many facets of her practice with a focus on social connections, togetherness, and the possibilities of non-lingual communication. As a musician, she creates performances as site-specific responses, using a dynamic range of timbres and textures to amplify the acoustic qualities of a space, while also responding to the social conditions in the room. lololol sits down with Alice to discuss her experiences with sound, connection and the nonverbal.

Distal Fragments, collaboration with Environmental Performance Authority (2014), photo by Ssuhua Chen

Distal Fragments, collaboration with Environmental Performance Authority (2014), photo by Ssuhua ChenCan you talk about your work with sound in Tainan?

Before returning to Taiwan, Nigel [my partner] and I had performed in Melbourne, Europe and various places. We mostly played for audiences who were familiar with the scene of experimental music, and we appreciated the coming together of people from common backgrounds and shared languages. When we returned to Taiwan 12 years ago, there was a sense of freedom to go beyond the limitations we had previously put on ourselves. Sometimes we would perform for first time listeners of experimental music, which would bring a fresh energy, a new curiosity or excitement to the room. To this day, the audience for Ting Shuo Hear Say remains quite a mix—having people come from different musical backgrounds, it is a constant challenge to translate our music to a diverse crowd.

On top of running Ting Shuo Hear Say, you are also an art therapist and sound artist. Do these fields of work correlate with each other?

In my own practice, my work as an artist and art therapist go hand in hand. When I run group art therapy sessions, I try to respond to the various expectations or non-expectations in the room. I seek to ‘hold’ the variety of connections that make up the flow of energy in the group. This act of holding is important in my art practice as well, in which I explore how people connect with each other. I use voice as my instrument because it is the most direct communication, and when I perform, I feel I am creating a spider web for holding everything together.

When audiences come from different backgrounds, the weight of how each individual leans into the performance varies quite a lot. I try to tune into what is happening in the space, it could be emotions, states of being, or all kinds of body expressions—Is he relaxed? How much of her hair is standing up? Are they immersed in their own inner reflection or inner imagination? For me it is all these small observations that reveal the connections in the room. The observing process is not so much in the head, it is more empirical; by experience and practice, observations become heightened and there is a sensitive tuning process involved while I respond to the collective feeling and atmosphere in the space.

As a performer, how do you see your relationship with the audience?

There’s a saying, “Two step forward and one step back,” which gives me an image of someone perpetually getting somewhere, slowly. This image relates to my own interpretation of existential theory, which is that loneliness is the core of our existence, and while we come and go as individual bodies, a core aim of life is to connect with each other. During my performances, sometimes I do feel such a [connection between people].

For me, performing is not about selling an idea, it is a medium for people to transition together and enter a realm of suspended space and time. This process involves trusting that every individual has his or her value and identity. Trusting that in a finite time, togetherness will happen and will happen here, and afterwards, we will separate again.

My way of engaging with people is very different from the educational system in which I grew up. My school system upheld a hierarchy between teacher and students and maintained that students should be shaped or formed into a certain mold.

I believe that everyone is different, there is no unified way, and in my performances, the audience takes in something as their own reflection, their mirrored self, and directs this feedback into whatever they are thinking or whoever they are in that moment in time. After the performance, every individual takes away some residue from the collective experience.

Do you always work with an audience?

Sometimes, without an audience, I can work with images or texts in my head. Sometimes, there are from dreams I have had, stories I have read, or just inspirations from my own imagination. I once made a performance using a scene from a Haruki Murakami novel, which described a feeling of sinking down into the ocean, sinking down, losing breath, continually sinking, and so on. I did a couple performances with this departure point. Perhaps for me it is a sad narrative about someone who has lived a life not having their own say and feeling getting more and more choked up. What attracts me to such sorrow is its complexity.

Sometimes I find that images are able to describe what language cannot. The ocean, forests, the moon, and scenery…these are typical themes for poets and artists because there are no words that can quite describe them. I attempt to embody an image by putting it inside my body; I feel it and try to form it out. It is an attempt to translate something indescribable to other people. Whilst this process can be understood as a way of communication, it could also be understood more poetically as an artist putting her body in a very imaginative, emotional, complex state and performing it.

How do you describe your sound palette?

I do not listen to a lot of music, in fact, I find everyday sound much more fitting to my palette of sound--the bathroom fan, vertical roller gate, all the daily industrial or natural sounds that we live in--they embody a language that is honest and real. My voice is shaped by the soundscape of my environment.

After performing for many years, it is easy to become fixed, and I try to make myself more flexible. Sometimes I sense an intuition and there is a voice coming out; sometimes I mute that intuition and work with something else. Quite often I work with the feedback people give me about my performances. One of my lecturers from university had once commented that, in my work, silence is more important than the voice. His comment made me reflect on how to use time, how silence still holds certain attention, and carries the residue of the sound that had come before it. It holds an imagination that reflects back to the viewer, like a black mono painting or the blank spaces in Chinese painting.

How do you experience space and time in your work?

In my earlier work, during my university years, I performed a lot in stairwells, hallways, transitional spaces, as I worked with the idea of travelling. It was not a matter of going from one point to another; it was about the tunnel, the transitional process that happens in between. This practice of working in a perpetual cycle of suspended time and space is perhaps influenced by minimal music or drone-based stuff. Both Nigel and I in our 12 Dog Cycle band, and my other duo with Saxophonist Rosalind Hall, work with this idea. Someone had commented that our music always feels like it is starting and ending all the time, because we are constantly working against the flow, not following any situation and continually surprising ourselves.

Is there anything specific you are working on right now?

I have always wanted to develop my art therapy practice further. Since coming back to Taiwan, I have spent a lot of my time setting up Ting Shuo and more recently, I have been busy raising our child. But now I find my art practice is becoming more diverse—I have been running workshops for children from age 0 to 6 as well as for old people over ages 60 to 80. Next month, I am running workshops with people who are blind. Meanwhile, I am also working on my solo album, “Alice in Wonderland,” based on Lewis Carroll’s 12-chapter storybook. I will be working on this album and text/contemporary scores in the next few years.

(update / 2020.05.26)

☯ Alice Hui-Sheng Chang

Sound improviser, art therapist and co-founder of sound organization Ting Shuo Hear Say. Alice weaves between the many facets of her practice with a focus on social connections, togetherness, and the possibilities of non-lingual communication.

huishengchang.com

tingshuostudio.org

Sound improviser, art therapist and co-founder of sound organization Ting Shuo Hear Say. Alice weaves between the many facets of her practice with a focus on social connections, togetherness, and the possibilities of non-lingual communication.

huishengchang.com

tingshuostudio.org

lololol interviews #3: Nicholas Bussmann & Yan Jun

Nicholas Bussmann: I Do Games that Have Nothing to Win or Lose, It’s Just a Possibility.

Original video version was first presented at

JUT Museum’s “Lives” Exhibition Artist Talk on June 18, 2022

Text edited by Ficus X

中文訪談請按此

”Most of the time, when we search, we search for something we have lost. Sometimes we search for something we have yet to find. There are different ways of looking for something, different techniques for something we have lost than for something we have yet to find. At this moment you see me searching and it looks like I am searching for something I have lost. That is not true, I am just behaving like I am searching for something. I move around and try to imagine there might be something, but there is nothing I am searching for. “

—— Nicholas Bussmann

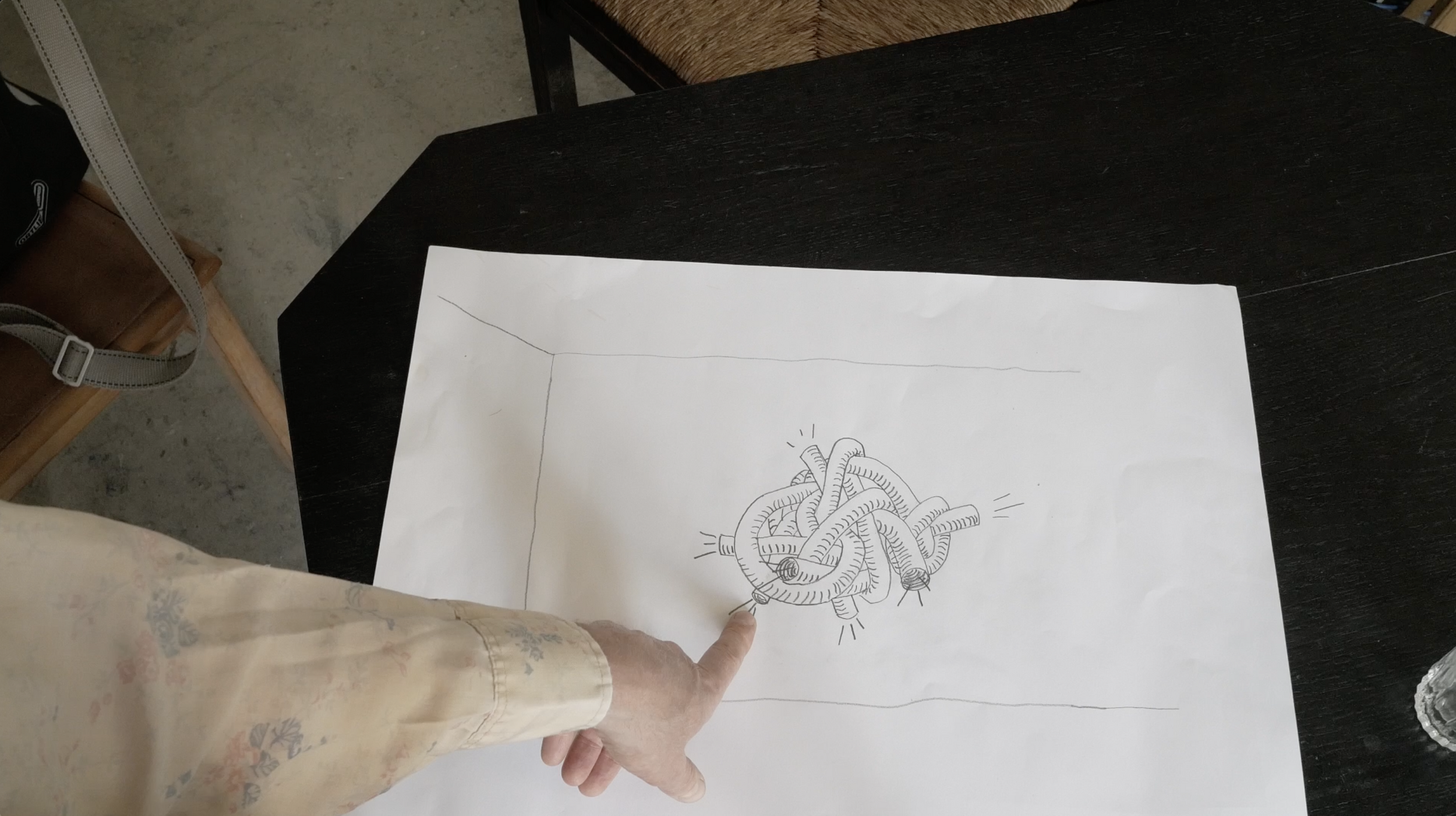

Sketch of Oral Archive of the Future Dead.

Photo of installation Wandering Dunes, Bussman points towards the words “Build a World”

Bussmann: This is the sketch of the Oral Archive of the Future Dead. This is the breathing of my mom, this is the breathing of a very good friend of mine, this is my youngest child’s breathing, and I don’t know who this other person is. This is a stranger who was asked to breathe, and this is my love.

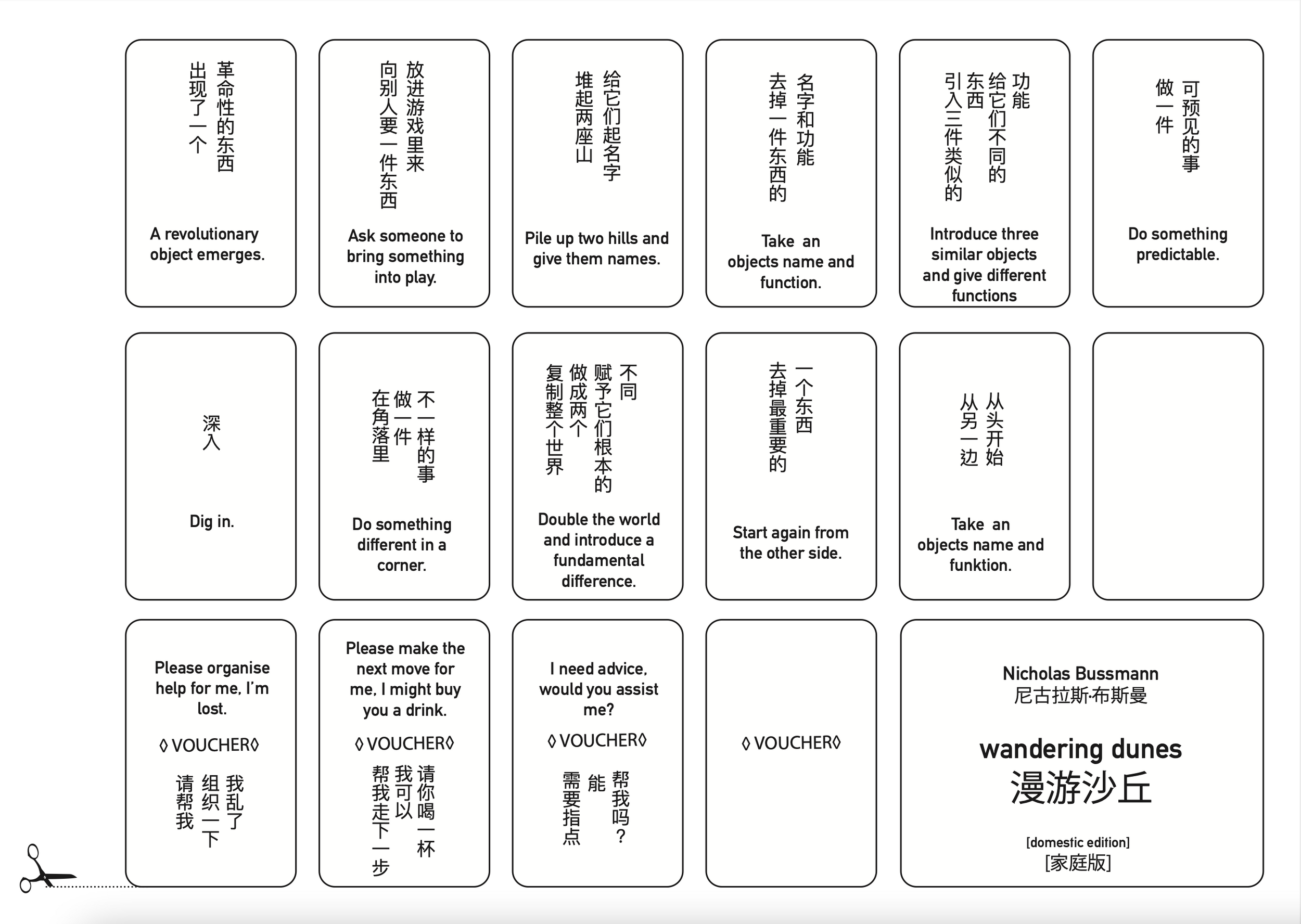

This [other] photo or a tableau vivant is of my installation and game Wandering Dunes, [which] consists of three sandbox tables, and a table with props you can play with. [On the Wall], there is an LED that creates an always changing light situation for the whole room. [The light spells] the sentence, “Build a world.”

That is what the game is about--to imagine and change the world. It is a game of two phases-- the first phase is about building a world, the second phase is about pushing time forward and in that moment, the change has to happen because time is just floating and going on and on. Change happens [while pursuing] questions of what happens, what is next, and happens after that. Here, between the tables, you see people who are holding newspapers and singing.

This is a choir singing the news. The Cottbusser choir, my multilingual choir. We developed a set of three algorithms together to sing the news. Major news / minor news, secret news, and the news blues. This became a part of the Wandering Dunes.

The new performance I am right now developing is basically growing out of Wandering Dunes, it is a work about marching together, and about basically the collective body and the body of the state.

I am a musician and I have spent most of my life doing music in concerts and recordings. It has been just seven years since I moved my work focus towards art. Music has one speciality, you can act, you can sing, you can play while you hear. You don’t have to deal with the semantics of a language, nor do you have to listen or completely understand. There is the synchronicity of action and reaction, between absorbing and giving at the same time. These techniques, which are special to music, in some ways can be translatable or used in different ways for forms of game structure.

I am very much interested in games structures, but I am not interested in games. I am not in awe of the idea of competitiveness, or what you believe games should be. I do games that have nothing to win and nothing to lose, it’s just a possibility.

This [other] photo or a tableau vivant is of my installation and game Wandering Dunes, [which] consists of three sandbox tables, and a table with props you can play with. [On the Wall], there is an LED that creates an always changing light situation for the whole room. [The light spells] the sentence, “Build a world.”

That is what the game is about--to imagine and change the world. It is a game of two phases-- the first phase is about building a world, the second phase is about pushing time forward and in that moment, the change has to happen because time is just floating and going on and on. Change happens [while pursuing] questions of what happens, what is next, and happens after that. Here, between the tables, you see people who are holding newspapers and singing.

This is a choir singing the news. The Cottbusser choir, my multilingual choir. We developed a set of three algorithms together to sing the news. Major news / minor news, secret news, and the news blues. This became a part of the Wandering Dunes.

The new performance I am right now developing is basically growing out of Wandering Dunes, it is a work about marching together, and about basically the collective body and the body of the state.

I am a musician and I have spent most of my life doing music in concerts and recordings. It has been just seven years since I moved my work focus towards art. Music has one speciality, you can act, you can sing, you can play while you hear. You don’t have to deal with the semantics of a language, nor do you have to listen or completely understand. There is the synchronicity of action and reaction, between absorbing and giving at the same time. These techniques, which are special to music, in some ways can be translatable or used in different ways for forms of game structure.

I am very much interested in games structures, but I am not interested in games. I am not in awe of the idea of competitiveness, or what you believe games should be. I do games that have nothing to win and nothing to lose, it’s just a possibility.

︎

Yan Jun Surpise Visit at Bussmann’s Studio

Wandering Dunes Domestic Version in collaboration with Yan Jun (https://grandprixdamour.com/Wandering-Dunes)

[The studio door opens, Yan Jun enters]

Bussmann (B): You didn’t knock.

Yan Jun (Y): We don’t.

B: Ah yeh, you just come in. I was surprised.

Y: That's okay, don’t be surprised. We need to do more meditation to reduce surprise and sudden reaction.

B: Is more meditation good for the music?

Y: It’s very good for the audience.

B: For the audience, yes, but for the musician, I’m not so sure.

Y: That’s okay, if your whole audience does meditation, you can do whatever you like.

B: But look, in the very end, you will end up doing what John Cage did, rolling the dice. We all become listeners and no action is necessary anymore.

Y: Okay, but I’m still talking about the audience. If you make your audience do meditation, you can play anything, and they will appreciate it.

B: That’s true.

Y: John Cage, I don’t know if he did meditation. Maybe he did it everyday, or maybe once a year.

B: I don’t know much about John Cage. As far as he said, he did it a lot, but he probably did it bad. [Refrains] I actually hardly know his name.

Y: I know his name very often, if you need one symbol in one realm, here is John Cage, here you have Jimi Hendrix, here you have Merzbow, here Joseph Beuys, and Michael Jackson there. Then you have everything.

B: It’s all men.

Y: Yes, yes..

[long pause]

B: So why do you make music?

Y: I was a music critic, I wrote a lot about music. But one day I realized all these people, 100%, or 99% of them just disappeared. They either stopped, disbanded, left, or just took a break. The scene was finished, so I had to do something. And also I didn’t want to write in this way as if, I know everything, the music critic has to know everything, but actually I don’t know everything, it is very difficult to play that role.

B: I understand, I wouldn't want to be a curator, because you need to know so much if you want to be good, and I’m not interested in knowing so much about music or art. I know a little and I know things that I like a lot, and I sometimes listen to certain things hundreds of times, while [there are] others I never unwrap.

Y: That is good for you. You don’t need the things you don’t need

B: Yes, it gives space. Also, it’s a territorial thing to have this knowledge about all the things, to be really informed. But I’m not really interested in knowing a territory, I’m alright with just observing how I move around in this field. I’m more interested in how I am trying to change the way I’m moving, than I know I’m moving in a certain direction to be part of another territory.

Y: So can I say, if you make a piece of art, you still keep a part of the art unknown.

B: Yes, but in art as well as in music, you know, I don’t really give a shit about the physical existence of it. The physical is just another tool, another instrument, it has no meaning.

Y: But in a music convention, people say you have to know your instrument and your material very well.

B: The topic of virtuosity is very strong in music, to really know your skills and be one of the best at it. I think virtuosity is very boring and overrated, because most of the things which interest me happen in relation to the audience and the performer, or between the performers, or between the audiences.

For instance, in art, there are people who visit an exhibition together and their interactions [are an instance of] things that interest me. [Coming back] to the idea of virtuosity, it is a way to claim superiority in a hierarchy, to claim that you are better than the others.

In a certain way it is true that you cannot escape virtuosity. [In life], you are always pushed in a direction of how people see you. ‘Ah, he can do this very good,’ ‘He is a very good singer,’ and suddenly, you are being moved into the direction of a professional cougher. ‘You coughed excellently in the last concert.’

Y: To become a professional cough artist, professional crying artist.

B: Yes there are people who are professional crying artists, I think it is a great profession.

Y: That’s different from a professional cello player, and you are a great cello improviser, how did you stop going in this direction?

B: I didn’t give up, I still play, I just play much less. It moved into a different place. It’s a difficult question, I adore the people who stick with their instrument and explore over a long time with many different people the vocabularies they can do with this instrument.

But then the idea of virtuosity comes up, you can’t escape it, you are doing this thing with one instrument, and you are getting better at it, and you are doing special techniques and so on, then you are a specialist doing something special in a special way. I think that is a bit of a trap.

Y: How about robots? There is one guy in Berlin who uses a robot to play piano. He’s the best.

B: You can’t say that really, it is impossible with robots. They are always at maximum possibility, it is always a failure.

Y: But it’s the best failure.

B: It’s a very good failure, because it is built for virtuosity. Well that’s not really true, because it may also get very hot from doing really fast stuff for a very long time. And then it has to slow down. So it also has some kind of fatigue of the muscles.

Bussmann (B): You didn’t knock.

Yan Jun (Y): We don’t.

B: Ah yeh, you just come in. I was surprised.

Y: That's okay, don’t be surprised. We need to do more meditation to reduce surprise and sudden reaction.

B: Is more meditation good for the music?

Y: It’s very good for the audience.

B: For the audience, yes, but for the musician, I’m not so sure.

Y: That’s okay, if your whole audience does meditation, you can do whatever you like.

B: But look, in the very end, you will end up doing what John Cage did, rolling the dice. We all become listeners and no action is necessary anymore.

Y: Okay, but I’m still talking about the audience. If you make your audience do meditation, you can play anything, and they will appreciate it.

B: That’s true.

Y: John Cage, I don’t know if he did meditation. Maybe he did it everyday, or maybe once a year.

B: I don’t know much about John Cage. As far as he said, he did it a lot, but he probably did it bad. [Refrains] I actually hardly know his name.

Y: I know his name very often, if you need one symbol in one realm, here is John Cage, here you have Jimi Hendrix, here you have Merzbow, here Joseph Beuys, and Michael Jackson there. Then you have everything.

B: It’s all men.

Y: Yes, yes..

[long pause]

B: So why do you make music?

Y: I was a music critic, I wrote a lot about music. But one day I realized all these people, 100%, or 99% of them just disappeared. They either stopped, disbanded, left, or just took a break. The scene was finished, so I had to do something. And also I didn’t want to write in this way as if, I know everything, the music critic has to know everything, but actually I don’t know everything, it is very difficult to play that role.

B: I understand, I wouldn't want to be a curator, because you need to know so much if you want to be good, and I’m not interested in knowing so much about music or art. I know a little and I know things that I like a lot, and I sometimes listen to certain things hundreds of times, while [there are] others I never unwrap.

Y: That is good for you. You don’t need the things you don’t need

B: Yes, it gives space. Also, it’s a territorial thing to have this knowledge about all the things, to be really informed. But I’m not really interested in knowing a territory, I’m alright with just observing how I move around in this field. I’m more interested in how I am trying to change the way I’m moving, than I know I’m moving in a certain direction to be part of another territory.

Y: So can I say, if you make a piece of art, you still keep a part of the art unknown.

B: Yes, but in art as well as in music, you know, I don’t really give a shit about the physical existence of it. The physical is just another tool, another instrument, it has no meaning.

Y: But in a music convention, people say you have to know your instrument and your material very well.

B: The topic of virtuosity is very strong in music, to really know your skills and be one of the best at it. I think virtuosity is very boring and overrated, because most of the things which interest me happen in relation to the audience and the performer, or between the performers, or between the audiences.

For instance, in art, there are people who visit an exhibition together and their interactions [are an instance of] things that interest me. [Coming back] to the idea of virtuosity, it is a way to claim superiority in a hierarchy, to claim that you are better than the others.

In a certain way it is true that you cannot escape virtuosity. [In life], you are always pushed in a direction of how people see you. ‘Ah, he can do this very good,’ ‘He is a very good singer,’ and suddenly, you are being moved into the direction of a professional cougher. ‘You coughed excellently in the last concert.’

Y: To become a professional cough artist, professional crying artist.

B: Yes there are people who are professional crying artists, I think it is a great profession.

Y: That’s different from a professional cello player, and you are a great cello improviser, how did you stop going in this direction?

B: I didn’t give up, I still play, I just play much less. It moved into a different place. It’s a difficult question, I adore the people who stick with their instrument and explore over a long time with many different people the vocabularies they can do with this instrument.

But then the idea of virtuosity comes up, you can’t escape it, you are doing this thing with one instrument, and you are getting better at it, and you are doing special techniques and so on, then you are a specialist doing something special in a special way. I think that is a bit of a trap.

Y: How about robots? There is one guy in Berlin who uses a robot to play piano. He’s the best.

B: You can’t say that really, it is impossible with robots. They are always at maximum possibility, it is always a failure.

Y: But it’s the best failure.

B: It’s a very good failure, because it is built for virtuosity. Well that’s not really true, because it may also get very hot from doing really fast stuff for a very long time. And then it has to slow down. So it also has some kind of fatigue of the muscles.

Yan Jun & Nicholas Bussmann in studio.

(update / 2022.06.26)

☯ Nicholas Bussmann

Nicholas Bussmann is an artist and musician. With a biographical background in Improvised Music, he creates conceptual frameworks and concrete scenarios for collective performances. At the center of his interest lies the ight and historically rooted connection between music, social practice and socialization.

https://www.discogs.com/artist/394378-Nicholas-Bussmann

Nicholas Bussmann is an artist and musician. With a biographical background in Improvised Music, he creates conceptual frameworks and concrete scenarios for collective performances. At the center of his interest lies the ight and historically rooted connection between music, social practice and socialization.

https://www.discogs.com/artist/394378-Nicholas-Bussmann

Nicholas Bussmann 是一位具有即興音樂創作背景的藝術家和音樂家,擅長未集體表演創造概念架構於具體場景。他最感興趣的是音樂、社會事件、以及社會化之間緊密且具有歷史淵源的連結。

☯ Yan Jun

a musician and poet based in beijing.

he works on experimental music and improvised music. he uses noise, field recording, body and concept as materials.

sometimes he goes to audience’s home for playing a plastic bag.

“i wish i was a piece of field recording.”

yanjun.org

www.subjam.org

a musician and poet based in beijing.

he works on experimental music and improvised music. he uses noise, field recording, body and concept as materials.

sometimes he goes to audience’s home for playing a plastic bag.

“i wish i was a piece of field recording.”

yanjun.org

www.subjam.org

☯ 顏峻

樂手,詩人,住在北京。

從事實驗音樂和即興音樂。

使用噪音、田野錄音、身體、概念作為素材。

他的作品通常很簡單,沒有什麼技巧,也不像音樂。有時候會去觀眾家演奏塑料袋。

“我希望我是一份田野錄音。”

樂手,詩人,住在北京。

從事實驗音樂和即興音樂。

使用噪音、田野錄音、身體、概念作為素材。

他的作品通常很簡單,沒有什麼技巧,也不像音樂。有時候會去觀眾家演奏塑料袋。

“我希望我是一份田野錄音。”