InnerEar 內耳

The innermost part of the vertebrate ear. The inner ear is responsible for sound detection and balance. Irregularity will cause symptoms such as nausea and headaches. Listen around you and convert the mechanical vibrations of the ear into neural signals. Practice mindful cultivation of the Inner Ear and ease the flow between the mechanical and the neurosensory.

Sonic Battlefield of Virtuous Character

Sonic Battlefield of Virtuous Character 聲響中的倫理抗衡

◎Sheryl Cheung

I Do Games that Have Nothing to Win or Lose, It’s Just a Possibility

I Do Games that Have Nothing to Win or Lose, It’s Just a Possibility

我的遊戲沒有贏家,也沒有輸家,只有可能性

◎Nicholas Bussmann and Yan Jun

Two step forward and one step back: Interview with Alice Hui-sheng Chang

向前走兩步,向後退一步

◎Alice Hui-sheng Chang

Gentle Sweeps in a Deep Abyss: Interview with Dino深淵裡的漣漪

Gentle Sweeps in a Deep Abyss: Interview with Dino深淵裡的漣漪◎Sheryl Cheung

Cosmopolitics in Sound

Cosmopolitics in Sound 聲音裡的宇宙政治

◎Sheryl Cheung

Internal Motivations

Internal Motivations 內部運動 ◎A Workshop by Sheryl Cheung, participants Anja Borowicz and Harriet Pittard

Electric Phantom

Electric Phantom 電魂

◎Itaru Ouwan

Meridian of Fortune

Meridian of Fortune 財經二周天

◎TEIHAKU

Terms*

Terms* 條款* ◎Chun Yin Rainbow Chan & Craig Stubbs-Race

Gentle Steps Tainan

Gentle Steps Tainan 躡步台南

◎Nigel Brown

Amplified trumpet, Propellers, Metal and Air

Amplified trumpet, Propellers, Metal and Air 電聲小號、螺旋槳,金屬和空氣

◎Sound of the Mountain

Year

Year 年

◎Jin Sangtae

︎Inner Ear

The recording is my unknown memory, even if the message from its source is forgotten Part II

錄音是我未知的記憶,即使源頭的信息已被遺忘(下篇)

Every experience of sound possesses its own unique spatial characteristics--whether it is the varying ways sound transitions into one another in space, or the distance in between. The interplay between sounds and their spatial attributes is an important part of my work.

In 2022, I was invited to create a work Corridor Under Construction at C-LAB Sound Lab, equipped with a 49 channel, 360 degree surround sound system.

Each time the system booted up, white noise was played to test whether every speaker was functioning properly. I personally enjoyed listening to this speaker testing process, because even though it's the same white noise, each speaker's different angle created variations in how the sound was heard, sometimes even with shifted pitches. As the same sound moved through the 49 speakers—ding, ding, ding—it felt distinct from each one.

I loved how the white noise surrounds the space, so I had the technician write down the playback sequence for the speakers to incorporate it into the piece. Next, I included a second white noise recorded while riding past a campus gate — of a nitrogen tank releasing gas. These two sounds created a layered dynamic in the composition.

![]()

For me, creating a work that relies entirely on pre-recorded sounds played through speakers felt less engaging, so it was important to also include live sound. From past experience, surround-sound performances move sound around the space, but the sound feels disconnected from the space itself. Instead, it is as if the sound transforms the venue into another environment entirely, transporting you another place. So In the process of arranging, I aimed to highlight unique acoustic qualities of different spaces. The composition revolved around the idea of scene transitions, including shifts between various spaces, sometimes using specific sounds to facilitate those transitions.

At the same time, I wanted to use certain sounds to draw attention back to the immediate space and the live experience. In the live performance of Corridor Under Construction, I experimented with turning speakers into instruments. By attaching aluminum foil to the speakers and playing specific frequencies, I made the foil vibrate. Audiences could hear the faint sound produced by the vibrating foil on the speaker, combined with the clanging of the metal stanchions and the soundscape from the 49 speakers.

In the performance, I also played a recording of the sound of stanchions. Then, I physically interacted with the barriers on-site, pulling them up and letting them retract with a clanging sound. This created a contrast for the audience, offering a direct comparison of hearing the recorded sound of the object, and then experiencing the same object live in the space.

In 2022, I was invited to create a work Corridor Under Construction at C-LAB Sound Lab, equipped with a 49 channel, 360 degree surround sound system.

Each time the system booted up, white noise was played to test whether every speaker was functioning properly. I personally enjoyed listening to this speaker testing process, because even though it's the same white noise, each speaker's different angle created variations in how the sound was heard, sometimes even with shifted pitches. As the same sound moved through the 49 speakers—ding, ding, ding—it felt distinct from each one.

I loved how the white noise surrounds the space, so I had the technician write down the playback sequence for the speakers to incorporate it into the piece. Next, I included a second white noise recorded while riding past a campus gate — of a nitrogen tank releasing gas. These two sounds created a layered dynamic in the composition.

For me, creating a work that relies entirely on pre-recorded sounds played through speakers felt less engaging, so it was important to also include live sound. From past experience, surround-sound performances move sound around the space, but the sound feels disconnected from the space itself. Instead, it is as if the sound transforms the venue into another environment entirely, transporting you another place. So In the process of arranging, I aimed to highlight unique acoustic qualities of different spaces. The composition revolved around the idea of scene transitions, including shifts between various spaces, sometimes using specific sounds to facilitate those transitions.

At the same time, I wanted to use certain sounds to draw attention back to the immediate space and the live experience. In the live performance of Corridor Under Construction, I experimented with turning speakers into instruments. By attaching aluminum foil to the speakers and playing specific frequencies, I made the foil vibrate. Audiences could hear the faint sound produced by the vibrating foil on the speaker, combined with the clanging of the metal stanchions and the soundscape from the 49 speakers.

In the performance, I also played a recording of the sound of stanchions. Then, I physically interacted with the barriers on-site, pulling them up and letting them retract with a clanging sound. This created a contrast for the audience, offering a direct comparison of hearing the recorded sound of the object, and then experiencing the same object live in the space.

The technology of ambisonics is designed to transport you elsewhere - I compare the experience to that of VR, which immerses you into another environment with the aid of a headset. The spaces where people experience VR are often designed to eliminate any sound characteristics, aiming to achieve the effect of VR completely overriding reality. Instead of using sound to transport people to another place, I personally prefer bringing sounds from elsewhere into the present space.

If we stick to the VR analogy, in sound, I lean more toward AR — my own preference is to bring external sounds into the present space. That is why for my performance at Sound Lab, I included acoustic sounds produced live, rather than relying solely on speakers. Acoustic sound inherently feels distinct in a way that ambisonic sound struggles to replicate.

When it comes to illusions, I prefer shadow puppetry over Hollywood’s ultra-realistic special effects.

Speaking of different kinds of illusions, I compare my preference to shadow puppetry, which allows the option to step in and out of the illusion, maintaining a tangible connection between the participant and the imaginary. I recall reading an article that discussed how audiences tend to have a better relationship with ‘obviously fake’ illusions, as they make the experience of fiction more comprehensible. In a sense, this creates a stronger sense of wonder. You could say I gravitate toward meta approaches.

(Update: 2025-03-08, This Interview Articles form lololol “Energy Index” project, Supported by National Culture and Arts Foundation.)

︎ Fangyi Liu

Fangyi Liu lives in Kaohsiung. He focuses on freestyle musical and tonal improvisation. Additionally, he remixes and edits field recordings as demonstration works. Liu's work highlights two major points. The first is about the human voice. The act of pronouncing sounds from different races and cultures encompasses not only language but also pre-linguistic sounds, distortions, and language lapses. Even unestablished pronunciations can convey signals or context to listeners. The second point is about environmental sound or soundscapes. People are constantly surrounded by sounds from both living and nonliving things. His major projects address the issues of sensing and recognizing environmental sounds. Liu employs various materials and methods to explore these two topics.

He also created a Facebook group called Cochlea to introduce musicians from different fields to new audiences. He has organized several performances to promote new audio experiences.

Fangyi Liu lives in Kaohsiung. He focuses on freestyle musical and tonal improvisation. Additionally, he remixes and edits field recordings as demonstration works. Liu's work highlights two major points. The first is about the human voice. The act of pronouncing sounds from different races and cultures encompasses not only language but also pre-linguistic sounds, distortions, and language lapses. Even unestablished pronunciations can convey signals or context to listeners. The second point is about environmental sound or soundscapes. People are constantly surrounded by sounds from both living and nonliving things. His major projects address the issues of sensing and recognizing environmental sounds. Liu employs various materials and methods to explore these two topics.

He also created a Facebook group called Cochlea to introduce musicians from different fields to new audiences. He has organized several performances to promote new audio experiences.

︎ 劉芳一

現居高雄。他特別著迷於各式物件的聲學細節,並習慣於日常搜集聲音,進行即興演奏或聲音拼貼,構成意義含糊的敘事。其作品形式包括作曲、裝置和演出。現為“三半規管”及高雄實驗音樂團體“Beniyaben”成員,同時擔任高雄聲音聆聽推廣單位《耳蝸》的管理人與實驗音樂會《耳集》的策劃者。

劉芳一曾擔任《伊人》(2015)、《此岸:一個家族故事》(2020)、《宿舍》(2021)等影片的聲音設計,並參與演出TIDF《虛舟記》擴延電影配樂、台東美術館聲音藝術節、KLEX吉隆坡實驗電影錄像音樂節、台北藝術節、斯德哥爾摩藝穗節、另翼之聲:台灣當代噪音、即興、前衛音樂等活動。他的展覽經歷包括麻豆大地藝術季、金馬賓館、台灣雙年展等。

現居高雄。他特別著迷於各式物件的聲學細節,並習慣於日常搜集聲音,進行即興演奏或聲音拼貼,構成意義含糊的敘事。其作品形式包括作曲、裝置和演出。現為“三半規管”及高雄實驗音樂團體“Beniyaben”成員,同時擔任高雄聲音聆聽推廣單位《耳蝸》的管理人與實驗音樂會《耳集》的策劃者。

劉芳一曾擔任《伊人》(2015)、《此岸:一個家族故事》(2020)、《宿舍》(2021)等影片的聲音設計,並參與演出TIDF《虛舟記》擴延電影配樂、台東美術館聲音藝術節、KLEX吉隆坡實驗電影錄像音樂節、台北藝術節、斯德哥爾摩藝穗節、另翼之聲:台灣當代噪音、即興、前衛音樂等活動。他的展覽經歷包括麻豆大地藝術季、金馬賓館、台灣雙年展等。

︎Inner Ear

The recording is my unknown memory, even if the message from its source is forgotten Part I

錄音是我未知的記憶,即使源頭的信息已被遺忘(上篇)

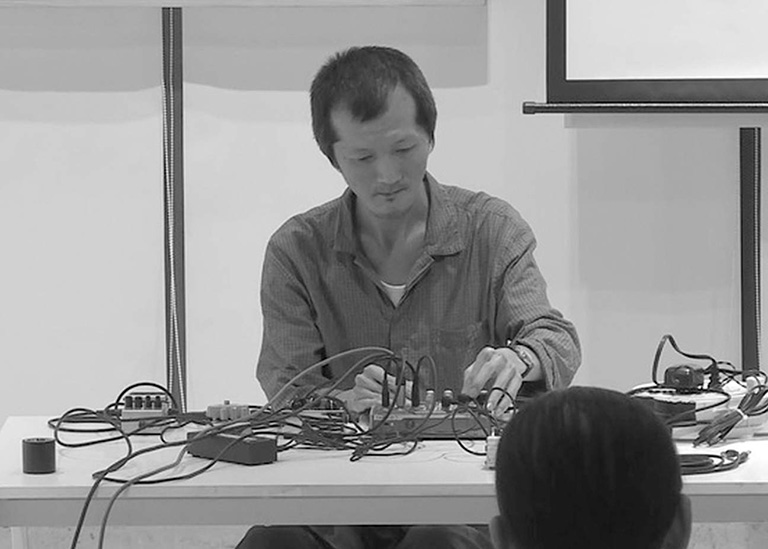

Artist Fangyi Liu. (Photo by Wu Yu Xuan)

When I first encountered experimental music, it was quite a shock.

One of my earliest experiences of experimental music was attending a performance by artist Alice Hui-Sheng Chang. Her powerful singing techniques extended beyond traditional vocalization methods by using vocal registers beyond the norm. The moment she produced sound, it felt as if the air had condensed and was then pierced by her voice. I was utterly shocked, thinking, So humans can make such sounds...After the show, I decided to buy her record and listened to it several times. The initial shock gradually transformed into appreciation and deeper connection to the music.

Later on, as I continued to search online for similar works to listen to, my first instinct was to start making something myself. I began by purchasing a relatively inexpensive synthesizer, the KORG Kaossilator. Its XY-coordinate control interface allowed me to manipulate and play sounds from its library with touch gestures. However, I quickly realized that it didn’t align with my needs or personality.

What really got me started in creating was buying a digital recorder. Once I had it, I felt compelled to record sounds wherever I went. Early on, I experimented with recording in my family’s bathroom. I recorded one track of playing with the bathtub and another of running water from the shower head. During these sessions, I’d play with elements at hand, like the shower head, water buckets, towel rack, and explore what sounds could be produced by water in this space.

While I wasn’t necessarily aiming for specific results, since I was making sounds, I thought I might as well let there be some variations. Of course, some of the sounds I recorded were based on prior experience. After all, with the many showers I had taken in that bathroom, I had a general idea of what sounds water in the bathtub could make. These recordings I made in my family’s bathroom eventually developed into my second album, Bathroom Meteorology released in 2015.

As a child, I loved rewinding cassette tapes to hear sound in reverse.

In making the first track of Bathroom Meteorology, I duplicated a recording, reversed its double and placed the two copies on top of each other. You can hear a reversed “thud” at the end of the track, which was originally the sound of myself striking the plastic bathtub. With the sound in reverse, it starts quietly, grows into a low-frequency sound, and suddenly erupts into a thud.

Reversed sound is a unique experience as it defies the natural acoustics of our world. In everyday life, I often hear sounds that resemble synthesizers, like birdsongs or the hum of electrical equipment, but a mechanically reversed sound does not naturally exist in everyday life.

In addition to my fascination with reversal, previous exposure to visual arts may have also been one of my influences when making this album. Visual symmetry, flipping or mirroring shapes, and overlapping layers -- to me, these common visual experiences can also be applied to the structure and development of sound.

For me, to record is an act of improvisation.

In many of my earlier works, I would record myself improvising with found objects, then edit in large sections. Oftentimes, I would also incorporate other recordings of sounds from my daily life; I have a habit of collecting materials, and when working on a piece, I would go through these recordings to find what I might need or use. Over time, I’ve since expanded to include more complex processes of arrangements.

From the moment of recording, I consciously select what sounds to capture. Later, when composing, I often preserve the improvisational essence of the original recording rather than deconstructing it. In the process of recording, there are many possibilities, and decisions are made based on aesthetic choices. The way sound takes shape, the factors that influence it, and even feelings in that moment all become key elements or conditions for documenting the present.

While broadly speaking, my everyday recordings may be referred to as ‘field recordings,’ I am aware that the term ‘field recordings’ belongs to a specific lineage of sound creation.

Anthropological or ecological field recordings tend to place greater emphasis on the source of the recorded sounds, serving the needs of academic research or preservation. In creative work, highlighting where a sound comes from—or what kind of sonic origins it is connected to—depends on the purpose of the piece and what the artist intends to emphasize.

In my own creative narrative, I don’t necessarily need to fully convey or preserve the original context of a sound’s source. Moreover, I tend to resist the idea that the sounds I record should be tied to their origins, as I see this as a potential limitation in artistic creation. This also relates to an individual’s creative habits. I record very often, but to be honest, I’m terrible at organizing my files.

Many times, after recording, I don’t specifically document where a particular sound came from. Sometimes, when I revisit recordings long after they’ve been made, I can vaguely recall when and where they were recorded and what they might have been related to. But this usually only happens when I’m digging through materials for a project and trying to piece together the time and place of those recordings.

A recording holds my unknown memory, even if the specific details of its origin are forgotten.

From the lineage of musique concrète artists, I prefer the work of Luc Ferrari. His iconic work titled Presque Rien ("Almost Nothing”) features the everyday sounds of a French fishing village. When listening to it, you may find it difficult to identify how exactly he employed the techniques of musique concrète. For Ferrari, musique concrète could preserve the original context of a sound while also allowing it to be appreciated purely for its sonic qualities.

Similarly, when I incorporate a sound into my work, I might make some subtle modifications, but I strive to retain its original state because it often makes the piece more interesting. When listening to field recordings, a sound can simultaneously serve as the audible trace of a specific source and be appreciated solely for its developments as sound.

Last year, I exhibited a multimedia installation The Recording is My Unknown Memory at Alien Art Center, Kaohsiung. When I was invited to create this new work, the curator asked for something that reflected a deeply personal and emotional side of the artist. They even framed it as a "letter to someone you love." It’s rare for a curatorial team to give such a direct thematic prompt.

While working on the project, I went through family photo albums. I saw childhood pictures—of places I went with my mom or photos with my dad—but I couldn’t recall the actual moments when those photos were taken. I was looking at the images but had no memory of them. I had forgotten those moments, but the photos remained. My mom told me that the child in the images was me, so I accepted that as truth. The record exists, I see it, and I acknowledge it. My mom would even add extra context or stories about what was happening in the photos.

Often, a recording can evoke a memory, even if you can’t quite place it no matter how hard you try. But I’ve come to terms with how it is —When I recorded it, it was tied to a specific source and the context of its creation. When I’m making art, connections are re-constructed in new ways. Memory, captured as a record—whether in photographs or sound—can be revisited, replayed, listened to, supplemented, or even reimagined. This process continues even if the specific details of origins are forgotten.

(Update: 2025-02-24, This Interview Articles form lololol “Energy Index” project, Supported by National Culture and Arts Foundation.)

︎ Fangyi Liu

Fangyi Liu lives in Kaohsiung. He focuses on freestyle musical and tonal improvisation. Additionally, he remixes and edits field recordings as demonstration works. Liu's work highlights two major points. The first is about the human voice. The act of pronouncing sounds from different races and cultures encompasses not only language but also pre-linguistic sounds, distortions, and language lapses. Even unestablished pronunciations can convey signals or context to listeners. The second point is about environmental sound or soundscapes. People are constantly surrounded by sounds from both living and nonliving things. His major projects address the issues of sensing and recognizing environmental sounds. Liu employs various materials and methods to explore these two topics.

He also created a Facebook group called Cochlea to introduce musicians from different fields to new audiences. He has organized several performances to promote new audio experiences.

Fangyi Liu lives in Kaohsiung. He focuses on freestyle musical and tonal improvisation. Additionally, he remixes and edits field recordings as demonstration works. Liu's work highlights two major points. The first is about the human voice. The act of pronouncing sounds from different races and cultures encompasses not only language but also pre-linguistic sounds, distortions, and language lapses. Even unestablished pronunciations can convey signals or context to listeners. The second point is about environmental sound or soundscapes. People are constantly surrounded by sounds from both living and nonliving things. His major projects address the issues of sensing and recognizing environmental sounds. Liu employs various materials and methods to explore these two topics.

He also created a Facebook group called Cochlea to introduce musicians from different fields to new audiences. He has organized several performances to promote new audio experiences.

︎ 劉芳一

現居高雄。他特別著迷於各式物件的聲學細節,並習慣於日常搜集聲音,進行即興演奏或聲音拼貼,構成意義含糊的敘事。其作品形式包括作曲、裝置和演出。現為“三半規管”及高雄實驗音樂團體“Beniyaben”成員,同時擔任高雄聲音聆聽推廣單位《耳蝸》的管理人與實驗音樂會《耳集》的策劃者。

劉芳一曾擔任《伊人》(2015)、《此岸:一個家族故事》(2020)、《宿舍》(2021)等影片的聲音設計,並參與演出TIDF《虛舟記》擴延電影配樂、台東美術館聲音藝術節、KLEX吉隆坡實驗電影錄像音樂節、台北藝術節、斯德哥爾摩藝穗節、另翼之聲:台灣當代噪音、即興、前衛音樂等活動。他的展覽經歷包括麻豆大地藝術季、金馬賓館、台灣雙年展等。

現居高雄。他特別著迷於各式物件的聲學細節,並習慣於日常搜集聲音,進行即興演奏或聲音拼貼,構成意義含糊的敘事。其作品形式包括作曲、裝置和演出。現為“三半規管”及高雄實驗音樂團體“Beniyaben”成員,同時擔任高雄聲音聆聽推廣單位《耳蝸》的管理人與實驗音樂會《耳集》的策劃者。

劉芳一曾擔任《伊人》(2015)、《此岸:一個家族故事》(2020)、《宿舍》(2021)等影片的聲音設計,並參與演出TIDF《虛舟記》擴延電影配樂、台東美術館聲音藝術節、KLEX吉隆坡實驗電影錄像音樂節、台北藝術節、斯德哥爾摩藝穗節、另翼之聲:台灣當代噪音、即興、前衛音樂等活動。他的展覽經歷包括麻豆大地藝術季、金馬賓館、台灣雙年展等。

︎Inner Ear

Sonic Battlefield of Virtuous Character

聲響中的倫理抗衡

Outer Pulsation #6, Dino x Sheryl Cheung, 2019, Taipei underpass.

“Sound can be very immediate, when you are on a battlefield, when you are facing death, it is not a matter of visual signals—you hear sound first. And perhaps, when in doubt, you will look for the source of the sound and stare at it, deciphering whether what you heard was real or not. Of course, there are those who are more visually-oriented, but the majority of ordinary people listen first, and use their eyes to seek validation. And that is something very unromantic.” -Dino1

To reach this auditory proximity to truth, Dino once quoted Confucius to describe what he does as a noise performer, “to live with unquestionable virtue..to end at one’s own excellence.2” With the time on stage by nature finite, Dino insisted each performance was an end to itself. To achieve excellence on stage is to enter a state of clear moral being and act by unquestionable goodness. He defined this goodness as a way of living in which all calculations are suspended and reflexive habits dulled. Fellow Taiwanese transdisciplinary artist and writer Lin Chi-wei once associated Dino’s sound practice with the traditional motive to detach oneself from worldliness, “What truly supports the value of "literati" is their life attitude…to transcend the entanglement between desire and reality, and allow the ‘real’ natural energy to flow into the small crafts of the world.3”

To align oneself with this immediate energy of life, Dino’s music can be best described as a wandering consciousness of will pitted against the invisible phenomenon of noise. There is no thinking and only doing as he “suppresses the never-ending feedback4” running through his no-input set of audio mixer and analog effect pedals. In face of the raw force of electronic noise-both as his phenomenological opponent and creative material- he controlled sound in a manner to cultivate his moral character. In his self-recorded tape “Song of Death” from 1997 5, a wet, rhythmic pulse continuously runs through his electronic circuit with effortless fluidity and resurfacing with a changing facade, like a meditation on transformation. Dino continued this alchemic process between the sound and self in varying dynamic range throughout his career. Of the few times I saw him on stage, Dino would perform with such understated showmanship, sitting still with minute hand movements tinkering analog controls. As a listener, it was easy to forget about his mortal corporeality. During his shows, I would often stare into the ceiling as sound embodied the space to realize itself as what 19th century philosopher Józef Maria Hoene-Wroński defined music as “the corporealization of intelligence that is in sound.6”

![]() Group photo at Dino’s residence in 2019 (from left to right: Jyun Ao Ceasar, Sheryl Cheung, Dino)

Group photo at Dino’s residence in 2019 (from left to right: Jyun Ao Ceasar, Sheryl Cheung, Dino)

In a solo performance at Revolver in 20187, a spattering of electronic feedback emerged, transformed, overlapped and/or died out before forming any definable structure. Between the original trigger and its shadows, space slowly opened up into a trance-like melody that emerged like a phoenix. Even as a recording, the listening experience causes a sense of spatial disorientation. Dino explained, “The kind of music I do is simple…only the first beat of sound you hear is real and the rest is fake, created by effects.8” As a listener, Dino’s psychoacoustic motivation created a flux state of consciousness that suspended my cognitive reflexes as a listening body, where it became difficult to ground perception in any other dimension other than sound.

In a Taipei underpass, I had a chance in 2019 to perform with Dino as part of Outer Pulsation, a guerrilla noise series organized by Chia-Chun Xu and folks from Senko Issha9. Culturally referencing the traditional Qigong anecdote to perceive the inner body as a pastoral landscape, I ran found recordings of rubble, metal and water through different filters and gates back and forth, at times to rub out their material references to reality, and in other moments seeking to build color with different elemental timbres. Meanwhile, Dino manipulated his no-input feedback into a high-pitched reed-like pressure as if playing a suona. He continued to play in this improvisational manner without melody or narrative, insisting on a minimalism that was searching for an opportunity for pure encounter. In moments when sounds were most indescribable and formless, sonic trajectories of power found space for conversation.

Dino’s romantic sentiment about sound provides an opportunity to trust in its boundlessness and seek direct engagement with its dynamic, transformative power. As described by Lin, “In the midst of chaos, Dino crafts a unique calm and simplicity that emanates from nowhere—an endless, yet intriguing silence that defines the very essence of music10.” Dino's approach to listening is an invitation to step into a realm where sound becomes the medium for profound, unspoken conversations with the self and the universe.

Group photo at Dino’s residence in 2019 (from left to right: Jyun Ao Ceasar, Sheryl Cheung, Dino)

Group photo at Dino’s residence in 2019 (from left to right: Jyun Ao Ceasar, Sheryl Cheung, Dino)In a solo performance at Revolver in 20187, a spattering of electronic feedback emerged, transformed, overlapped and/or died out before forming any definable structure. Between the original trigger and its shadows, space slowly opened up into a trance-like melody that emerged like a phoenix. Even as a recording, the listening experience causes a sense of spatial disorientation. Dino explained, “The kind of music I do is simple…only the first beat of sound you hear is real and the rest is fake, created by effects.8” As a listener, Dino’s psychoacoustic motivation created a flux state of consciousness that suspended my cognitive reflexes as a listening body, where it became difficult to ground perception in any other dimension other than sound.

In a Taipei underpass, I had a chance in 2019 to perform with Dino as part of Outer Pulsation, a guerrilla noise series organized by Chia-Chun Xu and folks from Senko Issha9. Culturally referencing the traditional Qigong anecdote to perceive the inner body as a pastoral landscape, I ran found recordings of rubble, metal and water through different filters and gates back and forth, at times to rub out their material references to reality, and in other moments seeking to build color with different elemental timbres. Meanwhile, Dino manipulated his no-input feedback into a high-pitched reed-like pressure as if playing a suona. He continued to play in this improvisational manner without melody or narrative, insisting on a minimalism that was searching for an opportunity for pure encounter. In moments when sounds were most indescribable and formless, sonic trajectories of power found space for conversation.

Dino’s romantic sentiment about sound provides an opportunity to trust in its boundlessness and seek direct engagement with its dynamic, transformative power. As described by Lin, “In the midst of chaos, Dino crafts a unique calm and simplicity that emanates from nowhere—an endless, yet intriguing silence that defines the very essence of music10.” Dino's approach to listening is an invitation to step into a realm where sound becomes the medium for profound, unspoken conversations with the self and the universe.

* All the photos are taken by Xia Lin.

1 Cheung, Sheryl. “Gentle Sweeps in a Deep Abyss: Interview with Dino.” Art Asia Pacific, March 26, 2019. https://artasiapacific.com/ideas/gentle-sweeps-in-a-deep-abyss-interview-with-dino

2 Kaplan, Kyle. 2017. “Made Here - Dino.” YouTube Website. Retrieved Dec 7, 2023. (http://youtube.com).

3 My original translation of Lin Chi-Wei’s “The Frame of Modernity and Beyond – The Lifework of Hsieh Tehching, Hsieh Ying-Chun, Wu-Chong-Wei, Graffitist Hwang, DINO and Tsai-Show-Zoo,” 2013. http://www.linchiwei.com/archives/1777

4 Kaplan. Ibid.

5 誠意重, 2021. “Dino 廖銘和 - Song of Death 死亡之歌 (1997).” YouTube Website. Retrieved Dec 3, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eF8YUz3wt1Y&t=905s.

6 Edgar Varese in his essay “The Liberation of Sound” Chou, Wen-chung (Eds.) The Liberation of Sound. Perspective of New Music, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Autumn - Winter, 1966), pp.19. https://music.arts.uci.edu/dobrian/CMC2009/Liberation.pdf

7 Dino, Senko Issha Live. Senko Issha, Nov 17, 2018. https://senko-issha.bandcamp.com/album/senko-issha-live

8 Cheung, Ibid.

9 誠意重, 2023. ”Outer Pulsation #6, Dino 廖銘和 x Sheryl Cheung 2019.8.10.” YouTube Website. Retrieved 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xd9sGa4ba8Y&t=693s

10 My original translation of Lin’s Chinese text. Lin. Ibid.

Other references

TKG+ Projects. 2023. “TKG+ Projects|物・自・造・_ creN/Ature|Dino X 吳牧青 Wu Muching.” Youtube Website. Retrieved 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g0IiT_-lZdA

Dawang, Huang. “Slowly Circling Around on a Bicycle: Dino and His Era of Noise.” Feb 29, 2022. Artouch. https://artouch.com/art-views/content-58691.html

Jyun Ao Caesar. “Underground Experimental Music in Taiwan.” Laoban Records. Oct 25, 2020. https://www.laobanrecords.com/post/underground-experimental-music-in-taiwan

Chia-Chun Xu. ”Re-think the Vitality of the Local Audio Scenes in The Post-Pandemic Era.“ Noman’s Land. Feb 12, 2023. https://www.heath.tw/nml-article/re-think-the-vitality-of-the-local-audio-scenes-in-the-post-pandemic-era/

(Update: 2024-05-21)

1 Cheung, Sheryl. “Gentle Sweeps in a Deep Abyss: Interview with Dino.” Art Asia Pacific, March 26, 2019. https://artasiapacific.com/ideas/gentle-sweeps-in-a-deep-abyss-interview-with-dino

2 Kaplan, Kyle. 2017. “Made Here - Dino.” YouTube Website. Retrieved Dec 7, 2023. (http://youtube.com).

3 My original translation of Lin Chi-Wei’s “The Frame of Modernity and Beyond – The Lifework of Hsieh Tehching, Hsieh Ying-Chun, Wu-Chong-Wei, Graffitist Hwang, DINO and Tsai-Show-Zoo,” 2013. http://www.linchiwei.com/archives/1777

4 Kaplan. Ibid.

5 誠意重, 2021. “Dino 廖銘和 - Song of Death 死亡之歌 (1997).” YouTube Website. Retrieved Dec 3, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eF8YUz3wt1Y&t=905s.

6 Edgar Varese in his essay “The Liberation of Sound” Chou, Wen-chung (Eds.) The Liberation of Sound. Perspective of New Music, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Autumn - Winter, 1966), pp.19. https://music.arts.uci.edu/dobrian/CMC2009/Liberation.pdf

7 Dino, Senko Issha Live. Senko Issha, Nov 17, 2018. https://senko-issha.bandcamp.com/album/senko-issha-live

8 Cheung, Ibid.

9 誠意重, 2023. ”Outer Pulsation #6, Dino 廖銘和 x Sheryl Cheung 2019.8.10.” YouTube Website. Retrieved 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xd9sGa4ba8Y&t=693s

10 My original translation of Lin’s Chinese text. Lin. Ibid.

Other references

TKG+ Projects. 2023. “TKG+ Projects|物・自・造・_ creN/Ature|Dino X 吳牧青 Wu Muching.” Youtube Website. Retrieved 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g0IiT_-lZdA

Dawang, Huang. “Slowly Circling Around on a Bicycle: Dino and His Era of Noise.” Feb 29, 2022. Artouch. https://artouch.com/art-views/content-58691.html

Jyun Ao Caesar. “Underground Experimental Music in Taiwan.” Laoban Records. Oct 25, 2020. https://www.laobanrecords.com/post/underground-experimental-music-in-taiwan

Chia-Chun Xu. ”Re-think the Vitality of the Local Audio Scenes in The Post-Pandemic Era.“ Noman’s Land. Feb 12, 2023. https://www.heath.tw/nml-article/re-think-the-vitality-of-the-local-audio-scenes-in-the-post-pandemic-era/

(Update: 2024-05-21)

︎ Sheryl Cheung

Sheryl Cheung works between experimental sound compositions, abstract scoring and performances to explore a material concept of life. Perceiving life as a force, a mobility that drives our innate persistence to live, she explores how active listening (working with sound) can be a mind and body practice to negotiate different noises of the world.

https://soundcosmology.cargo.site/

Sheryl Cheung works between experimental sound compositions, abstract scoring and performances to explore a material concept of life. Perceiving life as a force, a mobility that drives our innate persistence to live, she explores how active listening (working with sound) can be a mind and body practice to negotiate different noises of the world.

https://soundcosmology.cargo.site/

︎Inner Ear

Nicholas Bussmann: I Do Games that Have Nothing to Win or Lose, It’s Just a Possibility.

Original video version was first presented at

JUT Museum’s “Lives” Exhibition Artist Talk on June 18, 2022

Text edited by Ficus X

中文訪談請按此

”Most of the time, when we search, we search for something we have lost. Sometimes we search for something we have yet to find. There are different ways of looking for something, different techniques for something we have lost than for something we have yet to find. At this moment you see me searching and it looks like I am searching for something I have lost. That is not true, I am just behaving like I am searching for something. I move around and try to imagine there might be something, but there is nothing I am searching for. “

—— Nicholas Bussmann

Sketch of Oral Archive of the Future Dead.

Photo of installation Wandering Dunes, Bussman points towards the words “Build a World”

Bussmann: This is the sketch of the Oral Archive of the Future Dead. This is the breathing of my mom, this is the breathing of a very good friend of mine, this is my youngest child’s breathing, and I don’t know who this other person is. This is a stranger who was asked to breathe, and this is my love.

This [other] photo or a tableau vivant is of my installation and game Wandering Dunes, [which] consists of three sandbox tables, and a table with props you can play with. [On the Wall], there is an LED that creates an always changing light situation for the whole room. [The light spells] the sentence, “Build a world.”

That is what the game is about--to imagine and change the world. It is a game of two phases-- the first phase is about building a world, the second phase is about pushing time forward and in that moment, the change has to happen because time is just floating and going on and on. Change happens [while pursuing] questions of what happens, what is next, and happens after that. Here, between the tables, you see people who are holding newspapers and singing.

This is a choir singing the news. The Cottbusser choir, my multilingual choir. We developed a set of three algorithms together to sing the news. Major news / minor news, secret news, and the news blues. This became a part of the Wandering Dunes.

The new performance I am right now developing is basically growing out of Wandering Dunes, it is a work about marching together, and about basically the collective body and the body of the state.

I am a musician and I have spent most of my life doing music in concerts and recordings. It has been just seven years since I moved my work focus towards art. Music has one speciality, you can act, you can sing, you can play while you hear. You don’t have to deal with the semantics of a language, nor do you have to listen or completely understand. There is the synchronicity of action and reaction, between absorbing and giving at the same time. These techniques, which are special to music, in some ways can be translatable or used in different ways for forms of game structure.

I am very much interested in games structures, but I am not interested in games. I am not in awe of the idea of competitiveness, or what you believe games should be. I do games that have nothing to win and nothing to lose, it’s just a possibility.

This [other] photo or a tableau vivant is of my installation and game Wandering Dunes, [which] consists of three sandbox tables, and a table with props you can play with. [On the Wall], there is an LED that creates an always changing light situation for the whole room. [The light spells] the sentence, “Build a world.”

That is what the game is about--to imagine and change the world. It is a game of two phases-- the first phase is about building a world, the second phase is about pushing time forward and in that moment, the change has to happen because time is just floating and going on and on. Change happens [while pursuing] questions of what happens, what is next, and happens after that. Here, between the tables, you see people who are holding newspapers and singing.

This is a choir singing the news. The Cottbusser choir, my multilingual choir. We developed a set of three algorithms together to sing the news. Major news / minor news, secret news, and the news blues. This became a part of the Wandering Dunes.

The new performance I am right now developing is basically growing out of Wandering Dunes, it is a work about marching together, and about basically the collective body and the body of the state.

I am a musician and I have spent most of my life doing music in concerts and recordings. It has been just seven years since I moved my work focus towards art. Music has one speciality, you can act, you can sing, you can play while you hear. You don’t have to deal with the semantics of a language, nor do you have to listen or completely understand. There is the synchronicity of action and reaction, between absorbing and giving at the same time. These techniques, which are special to music, in some ways can be translatable or used in different ways for forms of game structure.

I am very much interested in games structures, but I am not interested in games. I am not in awe of the idea of competitiveness, or what you believe games should be. I do games that have nothing to win and nothing to lose, it’s just a possibility.

︎

Yan Jun Surpise Visit at Bussmann’s Studio

Wandering Dunes Domestic Version in collaboration with Yan Jun (https://grandprixdamour.com/Wandering-Dunes)

[The studio door opens, Yan Jun enters]

Bussmann (B): You didn’t knock.

Yan Jun (Y): We don’t.

B: Ah yeh, you just come in. I was surprised.

Y: That's okay, don’t be surprised. We need to do more meditation to reduce surprise and sudden reaction.

B: Is more meditation good for the music?

Y: It’s very good for the audience.

B: For the audience, yes, but for the musician, I’m not so sure.

Y: That’s okay, if your whole audience does meditation, you can do whatever you like.

B: But look, in the very end, you will end up doing what John Cage did, rolling the dice. We all become listeners and no action is necessary anymore.

Y: Okay, but I’m still talking about the audience. If you make your audience do meditation, you can play anything, and they will appreciate it.

B: That’s true.

Y: John Cage, I don’t know if he did meditation. Maybe he did it everyday, or maybe once a year.

B: I don’t know much about John Cage. As far as he said, he did it a lot, but he probably did it bad. [Refrains] I actually hardly know his name.

Y: I know his name very often, if you need one symbol in one realm, here is John Cage, here you have Jimi Hendrix, here you have Merzbow, here Joseph Beuys, and Michael Jackson there. Then you have everything.

B: It’s all men.

Y: Yes, yes..

[long pause]

B: So why do you make music?

Y: I was a music critic, I wrote a lot about music. But one day I realized all these people, 100%, or 99% of them just disappeared. They either stopped, disbanded, left, or just took a break. The scene was finished, so I had to do something. And also I didn’t want to write in this way as if, I know everything, the music critic has to know everything, but actually I don’t know everything, it is very difficult to play that role.

B: I understand, I wouldn't want to be a curator, because you need to know so much if you want to be good, and I’m not interested in knowing so much about music or art. I know a little and I know things that I like a lot, and I sometimes listen to certain things hundreds of times, while [there are] others I never unwrap.

Y: That is good for you. You don’t need the things you don’t need

B: Yes, it gives space. Also, it’s a territorial thing to have this knowledge about all the things, to be really informed. But I’m not really interested in knowing a territory, I’m alright with just observing how I move around in this field. I’m more interested in how I am trying to change the way I’m moving, than I know I’m moving in a certain direction to be part of another territory.

Y: So can I say, if you make a piece of art, you still keep a part of the art unknown.

B: Yes, but in art as well as in music, you know, I don’t really give a shit about the physical existence of it. The physical is just another tool, another instrument, it has no meaning.

Y: But in a music convention, people say you have to know your instrument and your material very well.

B: The topic of virtuosity is very strong in music, to really know your skills and be one of the best at it. I think virtuosity is very boring and overrated, because most of the things which interest me happen in relation to the audience and the performer, or between the performers, or between the audiences.

For instance, in art, there are people who visit an exhibition together and their interactions [are an instance of] things that interest me. [Coming back] to the idea of virtuosity, it is a way to claim superiority in a hierarchy, to claim that you are better than the others.

In a certain way it is true that you cannot escape virtuosity. [In life], you are always pushed in a direction of how people see you. ‘Ah, he can do this very good,’ ‘He is a very good singer,’ and suddenly, you are being moved into the direction of a professional cougher. ‘You coughed excellently in the last concert.’

Y: To become a professional cough artist, professional crying artist.

B: Yes there are people who are professional crying artists, I think it is a great profession.

Y: That’s different from a professional cello player, and you are a great cello improviser, how did you stop going in this direction?

B: I didn’t give up, I still play, I just play much less. It moved into a different place. It’s a difficult question, I adore the people who stick with their instrument and explore over a long time with many different people the vocabularies they can do with this instrument.

But then the idea of virtuosity comes up, you can’t escape it, you are doing this thing with one instrument, and you are getting better at it, and you are doing special techniques and so on, then you are a specialist doing something special in a special way. I think that is a bit of a trap.

Y: How about robots? There is one guy in Berlin who uses a robot to play piano. He’s the best.

B: You can’t say that really, it is impossible with robots. They are always at maximum possibility, it is always a failure.

Y: But it’s the best failure.

B: It’s a very good failure, because it is built for virtuosity. Well that’s not really true, because it may also get very hot from doing really fast stuff for a very long time. And then it has to slow down. So it also has some kind of fatigue of the muscles.

Bussmann (B): You didn’t knock.

Yan Jun (Y): We don’t.

B: Ah yeh, you just come in. I was surprised.

Y: That's okay, don’t be surprised. We need to do more meditation to reduce surprise and sudden reaction.

B: Is more meditation good for the music?

Y: It’s very good for the audience.

B: For the audience, yes, but for the musician, I’m not so sure.

Y: That’s okay, if your whole audience does meditation, you can do whatever you like.

B: But look, in the very end, you will end up doing what John Cage did, rolling the dice. We all become listeners and no action is necessary anymore.

Y: Okay, but I’m still talking about the audience. If you make your audience do meditation, you can play anything, and they will appreciate it.

B: That’s true.

Y: John Cage, I don’t know if he did meditation. Maybe he did it everyday, or maybe once a year.

B: I don’t know much about John Cage. As far as he said, he did it a lot, but he probably did it bad. [Refrains] I actually hardly know his name.

Y: I know his name very often, if you need one symbol in one realm, here is John Cage, here you have Jimi Hendrix, here you have Merzbow, here Joseph Beuys, and Michael Jackson there. Then you have everything.

B: It’s all men.

Y: Yes, yes..

[long pause]

B: So why do you make music?

Y: I was a music critic, I wrote a lot about music. But one day I realized all these people, 100%, or 99% of them just disappeared. They either stopped, disbanded, left, or just took a break. The scene was finished, so I had to do something. And also I didn’t want to write in this way as if, I know everything, the music critic has to know everything, but actually I don’t know everything, it is very difficult to play that role.

B: I understand, I wouldn't want to be a curator, because you need to know so much if you want to be good, and I’m not interested in knowing so much about music or art. I know a little and I know things that I like a lot, and I sometimes listen to certain things hundreds of times, while [there are] others I never unwrap.

Y: That is good for you. You don’t need the things you don’t need

B: Yes, it gives space. Also, it’s a territorial thing to have this knowledge about all the things, to be really informed. But I’m not really interested in knowing a territory, I’m alright with just observing how I move around in this field. I’m more interested in how I am trying to change the way I’m moving, than I know I’m moving in a certain direction to be part of another territory.

Y: So can I say, if you make a piece of art, you still keep a part of the art unknown.

B: Yes, but in art as well as in music, you know, I don’t really give a shit about the physical existence of it. The physical is just another tool, another instrument, it has no meaning.

Y: But in a music convention, people say you have to know your instrument and your material very well.

B: The topic of virtuosity is very strong in music, to really know your skills and be one of the best at it. I think virtuosity is very boring and overrated, because most of the things which interest me happen in relation to the audience and the performer, or between the performers, or between the audiences.

For instance, in art, there are people who visit an exhibition together and their interactions [are an instance of] things that interest me. [Coming back] to the idea of virtuosity, it is a way to claim superiority in a hierarchy, to claim that you are better than the others.

In a certain way it is true that you cannot escape virtuosity. [In life], you are always pushed in a direction of how people see you. ‘Ah, he can do this very good,’ ‘He is a very good singer,’ and suddenly, you are being moved into the direction of a professional cougher. ‘You coughed excellently in the last concert.’

Y: To become a professional cough artist, professional crying artist.

B: Yes there are people who are professional crying artists, I think it is a great profession.

Y: That’s different from a professional cello player, and you are a great cello improviser, how did you stop going in this direction?

B: I didn’t give up, I still play, I just play much less. It moved into a different place. It’s a difficult question, I adore the people who stick with their instrument and explore over a long time with many different people the vocabularies they can do with this instrument.

But then the idea of virtuosity comes up, you can’t escape it, you are doing this thing with one instrument, and you are getting better at it, and you are doing special techniques and so on, then you are a specialist doing something special in a special way. I think that is a bit of a trap.

Y: How about robots? There is one guy in Berlin who uses a robot to play piano. He’s the best.

B: You can’t say that really, it is impossible with robots. They are always at maximum possibility, it is always a failure.

Y: But it’s the best failure.

B: It’s a very good failure, because it is built for virtuosity. Well that’s not really true, because it may also get very hot from doing really fast stuff for a very long time. And then it has to slow down. So it also has some kind of fatigue of the muscles.

Yan Jun & Nicholas Bussmann in studio.

(Update: 2022-06-26)

︎ Nicholas Bussmann

Nicholas Bussmann is an artist and musician. With a biographical background in Improvised Music, he creates conceptual frameworks and concrete scenarios for collective performances. At the center of his interest lies the ight and historically rooted connection between music, social practice and socialization.

https://www.discogs.com/artist/394378-Nicholas-Bussmann

Nicholas Bussmann is an artist and musician. With a biographical background in Improvised Music, he creates conceptual frameworks and concrete scenarios for collective performances. At the center of his interest lies the ight and historically rooted connection between music, social practice and socialization.

https://www.discogs.com/artist/394378-Nicholas-Bussmann

Nicholas Bussmann 是一位具有即興音樂創作背景的藝術家和音樂家,擅長未集體表演創造概念架構於具體場景。他最感興趣的是音樂、社會事件、以及社會化之間緊密且具有歷史淵源的連結。

︎ Yan Jun

a musician and poet based in beijing.

he works on experimental music and improvised music. he uses noise, field recording, body and concept as materials.

sometimes he goes to audience’s home for playing a plastic bag.

“i wish i was a piece of field recording.”

yanjun.org

www.subjam.org

a musician and poet based in beijing.

he works on experimental music and improvised music. he uses noise, field recording, body and concept as materials.

sometimes he goes to audience’s home for playing a plastic bag.

“i wish i was a piece of field recording.”

yanjun.org

www.subjam.org

︎ 顏峻

樂手,詩人,住在北京。從事實驗音樂和即興音樂,使用噪音、田野錄音、身體、概念作為素材。他的作品通常很簡單,沒有什麼技巧,也不像音樂。有時候會去觀眾家演奏塑料袋。

“我希望我是一份田野錄音。”

樂手,詩人,住在北京。從事實驗音樂和即興音樂,使用噪音、田野錄音、身體、概念作為素材。他的作品通常很簡單,沒有什麼技巧,也不像音樂。有時候會去觀眾家演奏塑料袋。

“我希望我是一份田野錄音。”